Let me start my October series on monster movies by saying I am a human with a conflicted relationship to my own body. I am sick a lot. I was born premature and have never experienced robust health. Sometimes I think my body queered itself, constantly subverting the possibilities of wellness, but then again, it’s hard to extricate a body from things that have happened to it. The body is an unstable house even before people—be they doctors, rapists, lovers, or politicians—start breaking in. To say nothing of the stories we ingest.

I joke about my nineteenth-century constitution and melancholic humors, but I’m also a gender-nonconforming writer living in San Francisco at a very fractured time in the body politic. Watching a film from 1996 had me thinking a lot about 2017, not just about the siege of Trump’s “law and order” fascism (the film's Mexican biker bar, the Titty Twister, may be full of vampires but at least there are no nuclear codes) but about style and content, and the evolving ethical contracts between filmmakers and their audience. A prime example is the film’s opening scene in a gas station, where a Texas Ranger goes on a needless rant about the “Mongoloid” cooking hamburgers at a nearby diner. Tarantino, as usual, thinks shooting this asshole in the head is sufficient penance.

While I don’t believe in censorship, I know a cheap laugh and a low blow when I see one. At the same time, my project is about analyzing the human body through the non-human and subhuman, the infected and “turned,” the malformed and monstrous—imminently physical but nonetheless symbolic representations of what I will term the creaturely. While racism, ableism, and sexual predation are not outwardly readable traits, I tend to think our interest in the monstrous stem from those buried flaws rather than counter them. This is an admittedly Dorian Gray hypothesis, though I’d also argue that Frankenstein could have only been written by a woman. That’s a future blog post, though.

As for style, camp and debauchery have never been more relevant than under our orange fuhrer, as America casts a shadow that is as tragic as it is absurd. A circus is different from a fallen world, and their stories unfurl accordingly. I knew two things going into this film: (1) vampires show up (2) it is a genre hybrid that feels distinctly like two films in one. The threshold between Tarantino and Rodriguez' visions is the Mexican border, whereupon the film switches from an on-the-run American crime drama to a supernatural Mexican gore-gy. For now, I'll just say there's something nice about the simplicity of slaying our demons instead of having to reeducate-and-maybe-sorta-possibly-forgive them.

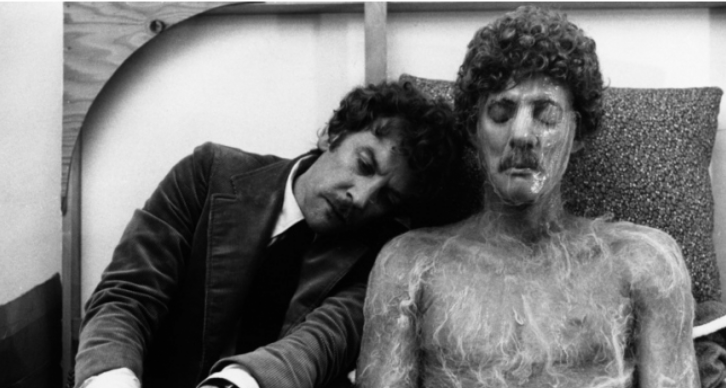

One of my leading interests in the creaturely is its use of the body as a site, not a vessel. American culture is not unique in thinking that the body is a house for the individual (make your own health care, wimps!) but our cinematic exports sure emphasize that the body is the place where everything happens. In an early scene, Tarantino peers at Clooney through a hole in his palm. Tarantino’s character, Richie, is a dangerously delusional sex offender and rapist, but those technicalities take a backseat to his paranoid-neurotic tics, borrowing more from Woody Allen than they knew in ’96. The eye-through-hand image stood out, visually telling us that here is a character who can only interface through the unreliable "knowledge" of his body. We are no different, of course, though it takes a show of deviance for us to notice.

Repulsion is one possible metric of a horror film’s efficacy, and both auteurs like to put humanity’s basest instincts at the center of our gaze, though I did find myself hoping Rodriguez was trying to beat Tarantino’s worst sensibilities out of him every time Richie was brutalized. Neither Tarantino nor Rodriguez pretend that Richie is Humbert Humbert, but they seem far too comfortable letting a young Juliette Lewis play the unwitting Lolita. For what it’s worth, Salma Hayek appears as the reversal of naive Lewis, playing a vampire-stripper whose hypnotic dance number picks up where Salome left off.