DIRECTOR: PHILIP KAUFMAN

WRITER: W.D. RICHTER

In psychiatry, there is a syndrome called the Capgras delusion. Sufferers become convinced that their acquaintances or loved ones have been replaced with identical imposters. It is generally associated with schizophrenia, though it can manifest in ailments as common as migraines and diabetes. We’re not certain of the neuroscience yet, but it appears that there is a disconnect between the “external” parts of recognition (face, gait, etc) and the “internal” part that recalls a loved one’s personality, beliefs, etc—or, perhaps, more simply, a disconnect between the limbic system (responsible for emotions) and the temporal cortex which regulates facial recognition. Patients with Capgras delusion do not have the appropriate galvanic skin response that should be automatic when we recognize faces. There is also a sister syndrome called Reduplicative Paramnesia, wherein the patient believes a place has been duplicated or relocated.

The 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is set in San Francisco, a place I have lived twice as an adult. For all its beauty and all its wealth, the city by the bay is not an easy place to live. At 24, I felt crushed by poverty and the sense that I must be, somehow, not only incapable but culpable. There were CEOs of start-ups my own age, to whom virtual strangers gifted millions of dollars. Over time I felt the Bay area chipping away at my definition of success, trying to make me in its image. It is easy to forgot how cutthroat San Francisco can be, given that it advertises itself as a kind of anti-NYC. But beneath the gorgeous parks, shining technology, and neo-futurists, the hustle is just as blistering.

I’d never seen a horror film set in a place I knew intimately. It was undeniably fun to recognize locations and feel a place I knew suddenly othered just as it was for the characters living in that iteration of my world. The eponymous body snatchers drift to earth as gelatinous space spores, attaching parasitically first to flowers and then humans. They quickly evolve into larger botanical pods, which incubate the duplicate body of one’s chosen host. But the real trouble (the real panic) began when the main characters realize not only what is happening, but that the San Francisco Police, the Health Department, and anyone else who could feasibly help them have already been turned. It’s nothing new in horror, this Cassandra complex where no one believes the herald of what’s-to-come. But the institutional disdain, paired with the high-wire emotional tenor of the film, sent me into a tailspin.

Actually I might be cool with a world with two Jeff Goldblums in it.

I’ve struggled with anxiety my whole life, but an assault and brutally dismissive police force (shoutout to SFPD!) led my symptoms to a tipping point in 2014. A few months later, I was diagnosed with panic disorder and agoraphobia—a diagnosis that had not occurred to me despite spells of paranoia and an inability to leave my bed even when my rational mind (to say nothing of my bladder) was begging me. All this to say: I have felt as though my body were no longer a place I could be. I have felt “snatched,” watching my body move across months like a desperate double. My double was scared of city buses, brunette men, a question asked a second time. She was also incapable of fighting people who were cruel to her. She began to believe there was always something bad lurking behind the next corner.

The breathless, sleepless panic that grips Matthew and Elizabeth (played by Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams, respectively) reminded me of myself at my worst: turned away by the police, lost to my friends, and taking great efforts to seem “fine” at work even though my morning commute required me to walk past my assailant’s street. When I slept, I woke up crying or thrashing. When I couldn’t sleep, I did drugs. I remember thinking I was like an empty grocery sack getting battered by the wind, accepting whatever form or direction the current imposed on me. Once your mind has decided that you can’t trust anyone and they won’t trust you, despair sets in.

By contrast, the duplicates in Invasion of the Body Snatchers are devoid of emotion. They have little resembling a personality, unless you count the determination of biological imperative. In one scene, a duplicate tells Elizabeth that “There is no need for hate now. Or love.” Donald Sutherland is tireless in his efforts to save SF and the human race, tireless in the way we are supposed to be when monumental crises arise. But I was not tireless in the wake of my assault. The SFPD taught me that no one will believe my truth no matter how painstakingly I told it. My assault taught me that leaving my body was not only possible, but at times necessary. Many times, Sutherland’s character rallies against his (human) peers’ despair, insisting they will survive the invasion if only they can stay awake. As viewers raised on hero cycles and happy endings, we want to believe him. Instead we watch his hope become increasingly irrelevant. That is, of course, the scariest part.

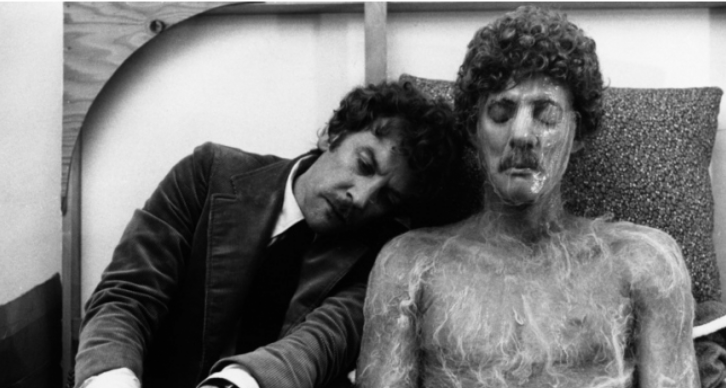

Sutherland and his gooey, hirsute double.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Some aspects of this movie are dated but the scene where the main characters discover half-formed pod people writhing and palpitating in birth (and/or death?) pangs is not one of them. The stickiness, the wheeziness, and the hairiness is visceral enough to pass muster. It was a very tactile scene, especially once that rake shows up.

Roger Ebert proposed that the numerous film remakes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers tend to be updated to popular paranoias of the time: the 1956 movie can be seen as a response to McCarthyism, the 1978 version to Watergate and Vietnam, and the 1993 version (simply titled Body Snatchers, Ebert’s fave) "might have been about the spread of AIDS.” There’s also a 2007 remake with Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig that Ebert suggests is about. . . very little.

Lastly, I am always relieved to see a movie where the impossible romantic tension remains impossible. Yes, “I love you” is said, but you can tell both characters are wondering why those words aren’t as magical as they anticipated. Hint: it’s because love won’t save them.